Back in 350 BC, Aristotle commented that Olympic victors were those who did not squander their powers by early overtraining. Few have heeded these words; overuse injuries remain front and center in our sports populations.

In the 1980s when we were investigating wrist pain in competitive gymnasts,

we noticed something strange: In many of these adolescent athletes, the

distal radius was short in proportion to the ulna, creating an impingement

of the triangular fibrocartilage.

In the 1980s when we were investigating wrist pain in competitive gymnasts,

we noticed something strange: In many of these adolescent athletes, the

distal radius was short in proportion to the ulna, creating an impingement

of the triangular fibrocartilage.

These patients were training more than 24 hours per week. We soon realized that overuse can suppress the physis, and not only in the wrist. It's one reason that many of the best female gymnasts stand only about 4'10".

The Manifestation of Overuse Injuries

The experience taught me that overuse injuries can manifest themselves in unexpected ways, so sports physicians must constantly be on the lookout.

Improvement as an athlete requires applying the optimum training load to bring about adaptation without causing harm.

That formula changes with the athlete's age and varies from sport to sport. While gymnasts' growth is stunted, 14- to 16-year-olds may end up with longer arms. In these athletes, the adaptations may make them better at their sports.

But in others, overuse can cause injuries that stop them in their tracks. This includes Osgood-Schlatter disease, an apophysis resulting from repetitive quadriceps contraction through the patellar tendon at its insertion upon the skeletally immature tibial tubercle. We see this a lot in September when kids return to school sports but are not properly adapted to the load.

In runners this time of year, we also tend to see stress fractures. These

are caused by a sudden increase in the dose of running. The intensity,

frequency, and duration determines the dose. And according to Wolff's

law, for every stress, the bone gets bigger and stronger. A stress fracture

occurs when the dose of stress exceeds the bone's capacity to adapt.

In runners this time of year, we also tend to see stress fractures. These

are caused by a sudden increase in the dose of running. The intensity,

frequency, and duration determines the dose. And according to Wolff's

law, for every stress, the bone gets bigger and stronger. A stress fracture

occurs when the dose of stress exceeds the bone's capacity to adapt.

Injury-Prevention Routines

Cross-country and track athletes must maintain a high-enough dose over the summer such that they can adapt to the training regimen in the fall. Working at UCLA in the late 1980s with Olympic medalist sprinters such as Florence Joyner, Danny Everett, Steve Lewis, and Mike Marsh, and with coaches like John Smith, I learned that every step up in intensity must be followed by a decrease. We called this "cyclical progression." For example, for runners, every increase of two tenths of a mile should be followed by a decrease of one tenth in the next run. A runner who starts at 3.0 miles should run 2.9 the next time, then 3.1, then 3.0, then 3.2, then 3.1, then 3.3 and so on.

Injury prevention warm-up routines such as the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) 11+ program can also reduce the risk for overuse injuries. In one study,[1] the FIFA 11+ reduced overuse injuries among teenage female soccer players by 47%.

Children run a lower risk for overuse injuries when they avoid superspecialization.[2] They should not focus on a single sport and instead alternate and experiment with multiple sports, at least until high school. Within sports, reasonable restrictions can also help prevent overuse injuries. In soccer, for example, I recommend not heading the ball below age 10 and only limited heading until age 14.

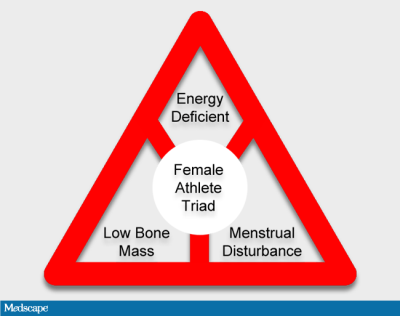

Overuse injuries are more common in female athletes and

are especially likely in young women who are suffering from the female

athlete triad: low energy availability with or without disordered eating, menstrual dysfunction,

and low bone mineral density.[3] Because they may make less estrogen, their bones may be weaker and more

susceptible to stress fractures. Older female athletes may run a similarly

elevated risk for stress

Overuse injuries are more common in female athletes and

are especially likely in young women who are suffering from the female

athlete triad: low energy availability with or without disordered eating, menstrual dysfunction,

and low bone mineral density.[3] Because they may make less estrogen, their bones may be weaker and more

susceptible to stress fractures. Older female athletes may run a similarly

elevated risk for stress

fractures if their estrogen levels have declined because of normal aging.

Because of problems like this, I look at the athlete in a very comprehensive manner. In our women's national soccer team, we frequently check dietary vitamin D and calcium. Low vitamin D levels have been associated with stress fractures.[4]

When Pain Does Not Equate Gain

One of the challenges for coaches and other sports professionals is that athletes vary in their ability to adapt to similar doses of exercise. For example, if you're a cross-country coach for a high school team, you'll have 14-year-olds who look like they're 12 and 14-year-olds who look like they're 20. The athletes who have not gone through puberty will experience pain at a lower dose of exercise than those who have gone through puberty.

Of course, not every pain means that the athlete needs to stop training. Some pain is simply a symptom of healthy adaptation. When it's a stress injury but not a stress fracture, athletes can back off, drop down in progression, cross-train, and allow the pain to get better. These are scalable processes.

But a very sharp pain means that the athlete should take a pause. And so does pain that progresses in its timing, from during the activity to after the activity and finally to before the activity. This sequence often signals a stress fracture.

The most common stress fractures cause pain in the hip, the thigh, the

tibia, and the outside of the foot. Significant hip pain in a young female

runner can be almost an emergency. I've often seen femoral neck stress

fractures go on to become displaced fractures. This can affect the blood

supply and cause avascular necrosis, leading to collapse of the femoral

head. That's a significant problem in a young person. So when female

athletes come to me with this type of pain, I get MRI scans as soon as possible.

The most common stress fractures cause pain in the hip, the thigh, the

tibia, and the outside of the foot. Significant hip pain in a young female

runner can be almost an emergency. I've often seen femoral neck stress

fractures go on to become displaced fractures. This can affect the blood

supply and cause avascular necrosis, leading to collapse of the femoral

head. That's a significant problem in a young person. So when female

athletes come to me with this type of pain, I get MRI scans as soon as possible.

Likewise, when an athlete reports tibial pain, I treat it as a stress fracture until proven otherwise. Fifth metatarsal fractures also start with significant pain and can quickly result in a displacement. When we see that dreaded line in the middle of the fifth metatarsal face, we're seeing something that has to be fixed right away.

Managing the dose of a training program can prove difficult at any level of recreation or competition. When I worked with US Navy Seals, I found that many were so aggressive, they wouldn't admit pain. They would get stress fractures and then get cut from the program.

On the other end of the continuum, I have worked with the LA Leggers running club. Some members start the season overweight or with low levels of vitamin D or estrogen. In this population, stress fractures can occur with training regimens of only a few miles per week. If you go from 0 to 6 miles per week, you can get the same effects as going from 30 to 90 miles per week.

That's why I tell all of the athletes I work with that the maxim "no pain, no gain" doesn't apply.

References

- Soligard T, Myklebust G, Steffen K, et al. Comprehensive warm-up programme to prevent injuries in young female footballers: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a2469.

- Myer GD, Jayanthi N, Difiori JP, et al. Sport Specialization, Part I: Does early sports specialization increase negative outcomes and reduce the opportunity for success in young athletes? Sports Health. 2015;7:437-442. Abstract

- Brown KA, Dewoolkar AV, Baker N, Dodich C. The female athlete triad: special considerations for adolescent female athletes. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:144-149. Abstract

- Burgi AA, Gorham ED, Garland CF, et al. High serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D is associated with a low incidence of stress fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:2371-2377. Abstract