Everything in medicine is connected, a principle I particularly keep in mind when I'm dealing with sports hernias (or athletic pubalgia), adductor injuries, and hip problems. I like to think of the three as a single syndrome: hip and groin issues.

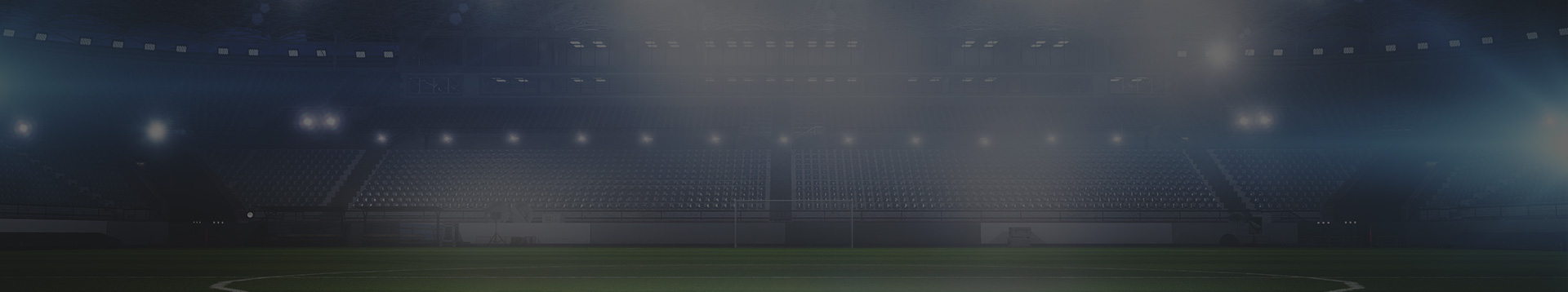

If you picture a Venn diagram, with each of these problems in a circle and all of the circles overlapping somewhat, you get a good image of the relationship. People may have one of these problems or two or three at the same time. So sports physicians should think of all of them when diagnosing pain or dysfunction in this area.

A whole series of problems can affect the hips, especially labral tears and cartilage issues. Then a little higher up, the ilioinguinal nerve or one of its branches can be impinged, or there may be a weakness in the rectus abdominis wall—what we call a sports hernia—which is a little different from a traditional hernia. Finally, you've got the issues that we have in terms of the adductor tendon.[1]

Hip and Groin Abnormalities in Athletes

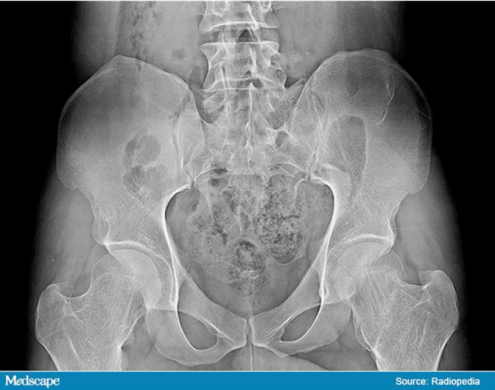

These problems are very common in elite athletes. In a study of x-rays from professional US male soccer players, we found a prevalence of 54.7% of hip and groin abnormalities.

|

|

In another ongoing study, we have so far found that 37.5% of the players on the US Men's National Soccer Team have had sports hernia surgery, and 12.5% of them have had bilateral sports hernia surgery. In 66% of these cases, they had a dual diagnosis. (Mandelbaum B, Silvers HJ, et al. Unpublished research.)

Sometimes one of these problems can evolve to affect the others. When athletes develop one of these problems, they begin to lose range of motion in their hips. Consequently, they put more force on their hips, and if they are 15 or 16 years old, they may suffer a mild slipped capital epiphysis. This gradually grows into a deformity, further restricting range of motion as they play, causing a labral tear, more weakness in the interior abdominal wall, and secondary adductor pain. This is ultimately a perfect storm!

Thus, there is a complex relationship between these problems. They stem from our evolution as quadrupeds who became bipeds dependent on the hip and the gluteus to keep us erect. Eccentric loading of muscles with torsion, load, and shear of the strong adductors may weaken the posterior abdominal wall and cause hypertrophy of the femoral neck as well as articular and labral abnormalities.

This is typically a gradual process. Hip and groin issues very rarely occur as a result of an acute injury, though occasionally the adductor pops off the pelvis and must be dealt with right away.

A Challenging Diagnosis

Diagnosis can be challenging because it's easy to focus on only one body part. There is no message that ever pops up to say, "You missed the other two." So you have to be very alert and systematic in taking the history. Did it happen in a particular day? Was there a pop? Was it sudden and acute or did it evolve in its intensity?

In my 27 years of practicing sports medicine, I have learned that it's hard for a single clinician to make a diagnosis in an efficient way. You need a hip specialist, a hip arthroscopist, a general surgeon who understands sports hernia, and a physical therapist. Our research so far suggests that we can reduce the incidence of these injuries by more than 25% in soccer. (Mandelbaum B, Silvers HJ, et al. Unpublished research.)

At the same time, a misdiagnosis can be costly. If you commit the athlete to taking 6 weeks off, and you're wrong and they need an operation, then you're 6 weeks behind the 8 ball.

So, proceed methodically. After taking a detailed history, speak to trainers and others who may have worked with the athlete to get their perspectives. Then begin a careful physical examination. Start by palpitating the abdomen, especially the lower third. Ask the athlete to identify the location of the pain. Circle it. If it radiates, put a mark where it radiates. Often, just by creating that diagram on the patient's abdomen, you can get a good understanding.

Range-of-Motion Maneuvers

Next, move on to dynamic testing. Ask the patient to do some crunches and see if there is pain. Then have the patient do a crunch with the leg in slight flexion. That puts a little load in certain areas of the abdomen. Next, have the patient crunch with a leg in flexion against resistance.

|

|

Move the patient through hip flexion, then resisted hip flexion, then adduction and abduction of the leg. Record which movements are the most painful and tender, as well as all other details as the patient goes through flexion, extension, internal external rotation, adduction, and abduction.

Look for pain associated with any of these range-of-motion maneuvers. Palpitate each of the muscles coming in and out of the pelvis, finding the points of maximum tenderness. A lot of athletes have asymmetric ranges of motion. If you find that the athlete is missing 15 degrees of external rotation and it's asymmetric, you're getting close to understanding where the problems are.

Diagnostic Imaging

Next, get to the x-ray. Do anteroposterior and lateral views (projections), looking for a femoroacetabular impingement. This can take the form of a cam defect, which is a thickening of bone on the lateral femoral neck and grinds the cartilage in the acetabulum. Or it can be a pincer deformity, in which extra bone extends out over the rim of the acetabulum, crushing the labrum and creating the impingement. Or you may find a combination of the two.[4]

In 2012, we looked at the x-rays taken during routine physicals of the US Men's National Soccer team and two Major League Soccer teams, and found that 68% of the players had cam deformities. In a professional women's team, 50% had these deformities. Most players didn't even know it.

When they become aware, players present with insidious, deep, strong pain localized to the pubic and adductor regions during activity. In soccer players, kicking the ball may cause a sharp pain. This pain may radiate. Thirty percent of males experience testicular pain, and 40% have tenderness in the adductor region.[2] The pain may become chronic and bilateral over time. (Mandelbaum B, Silvers HJ, et al. Unpublished research.)[3]

The next step is MRI, and most of the time we do this with gadolinium because we can better illuminate labral tears, loose bodies, and other characteristics of femoroacetabular impingement. We have a sports hernia protocol whereby we look specifically at the rectus and the insertion into the pelvis, the groin, and the adductor tendons coming in and out of the pelvis.

Finally, we put all of this together and figure out where the patient is in the Venn diagram. Do they have a labral tear, a cam deformity, a pincer deformity, a sports hernia, an impingement, or an adductor syndrome? Or do they have some combination? Sometimes they have all of it.

Treatment depends on these findings. I'll dive into those details in my next column.

References

- Meyers WC, Foley DP, Garrett WE, Lohnes JH, Mandlebaum BR. Management of severe lower abdominal or inguinal pain in high-performance athletes. PAIN (Performing Athletes with Abdominal or Inguinal Neuromuscular Pain Study Group). Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:2-8.

- Gerhardt MB, Romero AA, Silvers HJ, et al. The prevalence of radiographic hip abnormalities in elite soccer players. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:584-548.

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Femoroacetabular Impingement. http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=a00571 Accessed February 15, 2017.